Did you know that you can navigate the posts by swiping left and right?

Fable Tekno

02 Dec 2018 . Category . Comments #service #demo #hardware #outreach #fsharp #music

This post is my first contribution to the FsAdvent series, but it all started with an outreach event I’ve been doing for some years called Geek101.

Geek101 is a STEM field trip attached to a comic convention, and our goal there has been to get the kids engaged in STEM using robotics and cool HCI. I’ve been using a Kinect piano/theremin demo that’s gotten a bit stale (to me), so I thought I’d freshen it up with some F#/Fable magic.

Here’s the result:

Try online from a desktop or laptop!

So, how can we:

- Make music

- Controlled by Kinect

- Rendered in the browser

- Developed in Fable?

Music

There are quite a few options for making music in javascript. One that caught my eye in particular was Gibber, probably because it is prominently listed as a p5 library.

Gibber seems to be a family of projects sharing code, developed by Charlie Roberts and the gibber-cc organization. As a result, there’s a lot of documentation and tutorials available:

The interactive tutorials are probably the best way to get a feel for the capabilities and how to work with the library from a live coding/performance standpoint, which is what we are most interested in.

I started with the p5 version, tried other versions of the library, and eventually went back to the p5 version. I had some trouble getting other versions to work with p5 (needed for rendering Kinect tracking) and/or they were missing a key feature: synchronization. Synchronization aligns the clocks on all instruments so that when a new instrument is started, it starts at a musically appropriate time and on the beat.

Because Gibber is oriented towards live coding, javascript code generating music is eventually sent to eval using the Clock synchronization method.

This entails that p5-gibber is run in global rather than instance mode so that the correct Gibber functions can be found in global scope when eval executes.

This is what it looks like:

Gibber.Clock.codeToExecute.push( { code:"Kick().play( 55, Euclid( 5,8 ) )" } )

So how to interface with Fable? I started by using ts2fable on some typescript definition files of p5js to create a Fable foreign interface. Now we have static type checking for our p5 bindings!

For the Gibber library, we don’t have any typescript to start from. So I used a slightly dirty, but I think very useful trick:

- Open up global mode p5-gibber demo in chrome

- Set a breakpoint in

draw - Go to Global variable dropdown

- Select all variable names (including functions)

- Paste these into a file

- Filter out all non-functions

- Find/replace to add in all the needed Fable foreign interface code

I also used this strategy later to add more items to the p5 portion.

That’s why my interface file Fable.Import.p5.gibber.fs is a bit of a turducken:

- p5 typescript converted to fable using ts2fable

- Copy/paste hack to get gibber coverage

- Copy/paste hack to extend p5 a bit

I didn’t realize at first that I would need to be in global mode, so Fable.Import.p5.gibber.fs has a lot of instance mode applicability.

Also, you might be interested in the foreign interface I made of the p5 bindings from DefinitelyTyped using ts2fable (not very well tested!).

Ok, that’s the library, but how are we using it?

We consider that music has two dimensions, rhythm and pitch. Since Kinect returns spatial data, we need to re-represent that as temporal data for rhythm.

Gibber supports Euclidean rhythms which map rhythm patterns to two numbers.

Gibber’s Euclid(5,8) means 5 pulses across 8 notes and maps to this: “x.xx.xx.”

For Kinect integration, we map x/y coordinates of the right hand to those two numbers. We also map x/y coordinates of the right hand to pitch. To keep these two functionalities separate, we define “programming mode” for rhythm (delayed because of synchronization) and “performance mode” for pitch (played immediately). We’ll discuss the precise mapping below in the Kinect section.

Instruments

A basic drumkit has 4 components: kick, snare, hi-hat closed, and hi-hat open. Each component will require 1 person to operate. We choose to have 1 component per person so that person can have effects assigned to their left hand. The following sample code follows the same pattern: the first parameter is frequency, so is static (defines a characteristic of the instrument), and the second is a rhythm parameter.

Kick().play( 55, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

Snare().play(1, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

Hat().play(5000, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

Hat().play(30000, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

Like the rhythm instruments, pitched instruments have rhythm, which we program in the same way.

However, pitched instruments also have pitch, which can be represented by a single number for a bass line but needs 3 numbers for a chord. Mapping pitches to spatial coordinates is simple: we just define an origin and make sure the min/max of our pitch is appropriately scaled to the space of the left/right hand (defined in the Kinect section below).

Gibber allows us to real-time map pitch quantities to pitched instruments:

a = FM( 'bass' ).note.seq( function(){return Mouse.Y/1000} , Euclid( 5,8 ) )

Accordingly, once an instrument has “locked in” its rhythm, we use the right hand as an indicator of pitch in real time (immediate).

Mouse.Y is a special variable in Gibber, but it turns out that any variable will do as long as it is in global scope.

Because the variable representing pitch is called in a function, all we need to do is change that variable and the pitch will change accordingly.

We have three such global variables in index.html: bassPitch, melodyPitch1, and melodyPitch2.

We generate a third pitch for melodies using the two melody pitches as parameters.

So for the Bass instrument, we only need Y coordinates to define the pitch, but for the Melody instrument, we use both X and Y.

Effects

The left hand is used for effects using the same spatial mapping approach as pitched instruments.

One of the motivations for leaving effects to the left hand is that this demo is intended for kids. Kids will want to continually experiment with the sound, so giving them free rein over the left hand even after the right hand is locked in should help stabilize the group effort.

There’s no right/wrong answer it seems for what effects make sense for what instrument. Here are some reasonable presets with accompanying Gibber documentation and code.

Kick

a = Kick().play( 55, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

h = HPF()

h.cutoff=Mouse.X

a.fx.add(h)

r = Reverb()

r.roomSize=Mouse.Y

a.fx.add(r)

Snare

a = Snare().play(1, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

a.attack = Mouse.X

a.decay = Mouse.Y

Hat Closed

a = Hat().play(5000, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

f = Flanger()

f.rate = Mouse.Y

f.amount = Mouse.Y

f.feedback = Mouse.Y

a.fx.add(f)

h = LPF()

h.cutoff=Mouse.X

a.fx.add(h)

a.amp=6

Hat Open

a = Hat().play(30000, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

f = RingMod()

f.frequency = Mouse.Y

f.amp = Mouse.X

a.fx.add(f)

h = HPF()

h.cutoff=Mouse.X

a.fx.add(h)

Bass

a = FM( 'bass' ).note.seq( function(){return Mouse.Y/1000} , Euclid( 5,8 ) )

c = Crush()

c.bitDepth = Mouse.X

c.sampleRate = Mouse.Y

a.fx.add( c )

a.amp = Mouse.X

Melody

a = Synth2({ maxVoices:4, waveform:'PWM'} )

a.cutoff = Mouse.X

a.resonance = Mouse.Y

a.chord.seq( function(){return [ Mouse.X/1000, Mouse.Y/1000, (Mouse.X + Mouse.Y)/1000 ]}, Euclid( 5,8 ) )

Kinect/Mouse

Microsoft provides an SDK for Kinect v2, but since we are working in javascript, we need something more. Enter Kinectron, an application (using the MS SDK) that sends Kinect data over the network and a javascript library for working with it. The API is fairly simple and well documented. Basically, the Kinect simultaneously captures several streams of data, including RGB video, depth video, and tracked skeletons. It is the last one that most interest us, since we are going to use the position of the hands to determine the x/y coordinates for rhythm, pitch, and effects, and we are going to use the width of the shoulders to define the coordinate frame for each hand:

|

|

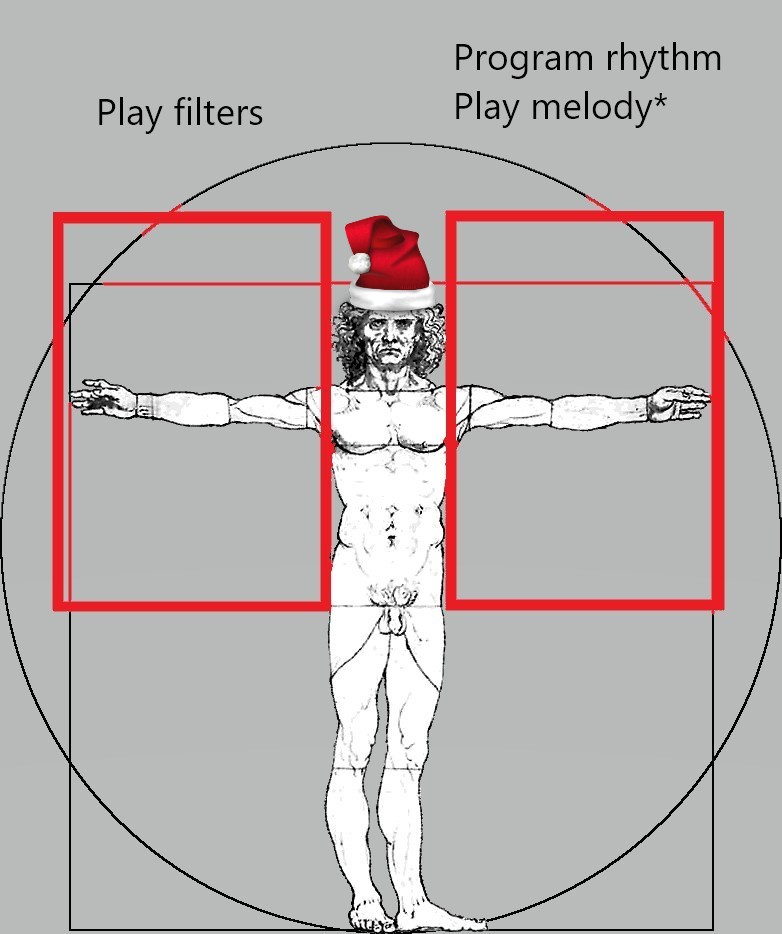

As you can see in the diagrams (based on the famous Vitruvian Man), the width of each coordinate frame is twice the width of the shoulders, and the height of each coordinate frame is three times the width of the shoulders. The coordinate frame itself is anchored at the base of the spine and each respective shoulder.

Hand positions are represented as x/y on [0,1] and then appropriately rescaled depending on the use. For example, Euclidean rhythm parameters are scaled by 16 (i.e., 16th notes), pitches are scaled by 20 (2.5 octaves), and effects are individually scaled based on their parameter ranges.

As with Gibber, I manually made a Fable foreign interface for Kinectron, though I relied more on the published API for Kinectron.

Kinectron, like Gibber, seems to want to be in global scope, so like p5 and Gibber, I included the scripts in the head of index.html.

Setting up Kinectron is as easy as:

let kinectron = new Kinectron( ip )

kinectron.makeConnection()

kinectron.startTrackedBodies(processFrame)

processFrame mostly draws things in P5 for us, but we note two points of interest.

First, Kinect gives us a few gestures for free, and we use those switch between programming and performance mode and to switch instruments:

//Lasso both hands (peace sign) is change instruments; closed hands (3) means rhythm programming; everything else is melody live performance

let bodyMode =

if body.rightHandState = 4 && body.leftHandState = 4 then

BodyMode.ChangeInstrument

elif body.rightHandState = 3 && body.leftHandState = 3 then

BodyMode.Programming

else

BodyMode.Performance

Second, Kinectron is generating events for us outside our Elmish message loop. If you haven’t heard of Elm or Elmish, you may want to check out a tutorial, because it’s a very simple and clean way to organize a GUI. The basic idea that is relevant here is that all changes to the state of the application, and therefore the interface, typically come from user-generated events like button presses. However, Elmish also supports subscriptions to external events. For our purpose, we more generically map to events and define a mechanism by which we can map any event to an Elmish message:

///External event wrapping a message

let mapEvent = Event<Msg>()

///Subscription on external events to bring them into Elmish message queue

let mapEventSubscription initial =

let sub dispatch =

let msgSender msg =

msg

|> dispatch

mapEvent.Publish.Add(msgSender)

Cmd.ofSub sub

We then use this mechanism in processFrame to send a message containing data about a body in the frame:

//Dispatch message for body state

mapEvent.Trigger ( Msg.Body( {Id=body.bodyIndex; Mode=bodyMode; LeftHand=leftX,leftY; RightHand=rightX,rightY} ) )

While all the above is well and good, developing a UI for the Kinect was rather tedious because it required getting up frequently and standing in front of the Kinect to test code. So for the purpose of development, and later I realized demonstration for those without a Kinect, I created a mouse interface that avoids the Kinect dependency.

In fact, the Vitruvian Man above with the Santa hat is from the mouse interface. The mouse interface uses a 100% image (resizing disabled) and some simple math to define the coordinate frames:

///Mouse mode active pattern for image relative coordinates of LEFT hand

let (|VitruvianLeft|_|) (x,y) =

let image = Browser.document.getElementById("vitruvian")

if image <> null then

let rect = image.getBoundingClientRect()

let xrel,yrel = x - rect.left,y - rect.top

if xrel > 65.0 && xrel < 320.0 && yrel > 220.0 && yrel < 600.0 then

Some( (xrel - 65.0 )/255.0, (yrel - 220.0)/380.0 ) //bound to [0,1]

else

None

else

None

I ended up using the same mapEvent approach above to work with native mouse events because putting the handler on the ReactElement resulted in messages like “Warning: This synthetic event is reused for performance reasons. If you’re seeing this, you’re accessing the method …”:

///Map native mouse move to Elmish messages

let onMouseMove (ev : Fable.Import.Browser.MouseEvent) =

mapEvent.Trigger ( Msg.MouseMove(ev.clientX,ev.clientY) )

null

Putting all the functionality in mouse mode, then wiring up the Kinect, resulted in a much faster development cycle.

The wiring in this case was just messages: in a handler for a mouse message I would construct and issue the same body message (shown above) that would be issued by the Kinect’s processFrame.

By simulating Kinect messages using the mouse, I was basically assured everything would work correctly once the same messages were being generated by the Kinect.

P5

P5 is a nice client-side javascript library for multimedia.

Canonically, one includes a setup function to initialize the application and a draw function that updates the application (i.e. per frame).

In our case, we include these two functions but only as empty functions, simply to force global mode, which I do in the head of index.html.

We handle setup in kinectronSketch, creating a canvas to draw on, setting it black, and globally setting a textAlignment parameter:

p5.createCanvas(canvasWidth, canvasHeight) |> ignore

p5.background(0.0 )

p5.textAlign( p5.Alignment.CENTER )

The rest of our p5 calls change color and draw joints for our tracked skeletons, with some variation for gestures:

if j.jointType = kinectron.HANDRIGHT && body.rightHandState = 2 then

p5.fill( 255.0 |> U4.Case1 )

p5.ellipse( j.depthX * canvasWidth, j.depthY * canvasHeight, 30.0,30.0) |> ignore

or draw text above the skeleton to indicate the hand coordinates, the instrument played, and the mode:

p5.textSize(20.0 ) |> ignore

p5.text(instrument.ToString() + " " + bodyMode.ToString() + " " + rs(leftX) + "," + rs(leftY) + "|" + rs(rightX) + "," + rs(rightY), body.joints.[kinectron.HEAD].depthX * canvasWidth, body.joints.[kinectron.HEAD].depthY * canvasHeight, 200.0,200.0 ) |> ignore

As these examples hopefully show, p5 is very easy to work with from Fable!

Fable

Developing in Fable these days is really lovely.

I’ve never been much a fan of javascript, but using Fable takes away most of the pain.

Typically where I run into trouble is when I’m trying to use a javascript library that doesn’t have a foreign interface already - particularly a large, ugly complicated javascript library.

When there’s a foreign interface and you’re using packages from NPM, there’s basically no friction at all.

Although there are a number of options for developing in Fable, I prefer to use VSCode with Ionide and Chrome debugger extensions (of course this assumes all dependencies are also installed). Using simple templates or more complex starter projects, one can code in F# while fable watches, transpiles, bundles with hot module replacement in Chrome. While it is possible to set F# breakpoints in VSCode, I prefer to set them in Chrome which supports breakpoints in both F#/Fable source maps and emitted javascript. It’s a really great way to build cross-platform apps for the web or Electron.

Wrapping up

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post. If you are already a part of the Fable community, please give p5 and gibber a go! If you’re familiar with F# but not Fable, give yourself a gift this holiday season and try it out.